Wondering why that number on the scale can’t seem to make up its mind? Up two pounds one day and down three pounds the next? Day-to-day fluctuations are totally normal, but that doesn’t make it any less frustrating when you’re trying to track true weight trends!

It’s normal for healthy individuals to experience short-term weight fluctuations of up to two to five pounds, mostly due to water weight. In this post we’re diving into the science behind these weight fluxes and why you shouldn’t worry!

Overview

Our body weight is made up of two different types of mass: fat-free mass and fat mass. Fat mass is the weight of our total body fat, whereas fat-free mass is the weight of our body’s non-fat components such as water, muscle, and bone. While muscle or fat changes contribute to longer-term weight trends, water is the most common culprit for short-term weight fluctuations.

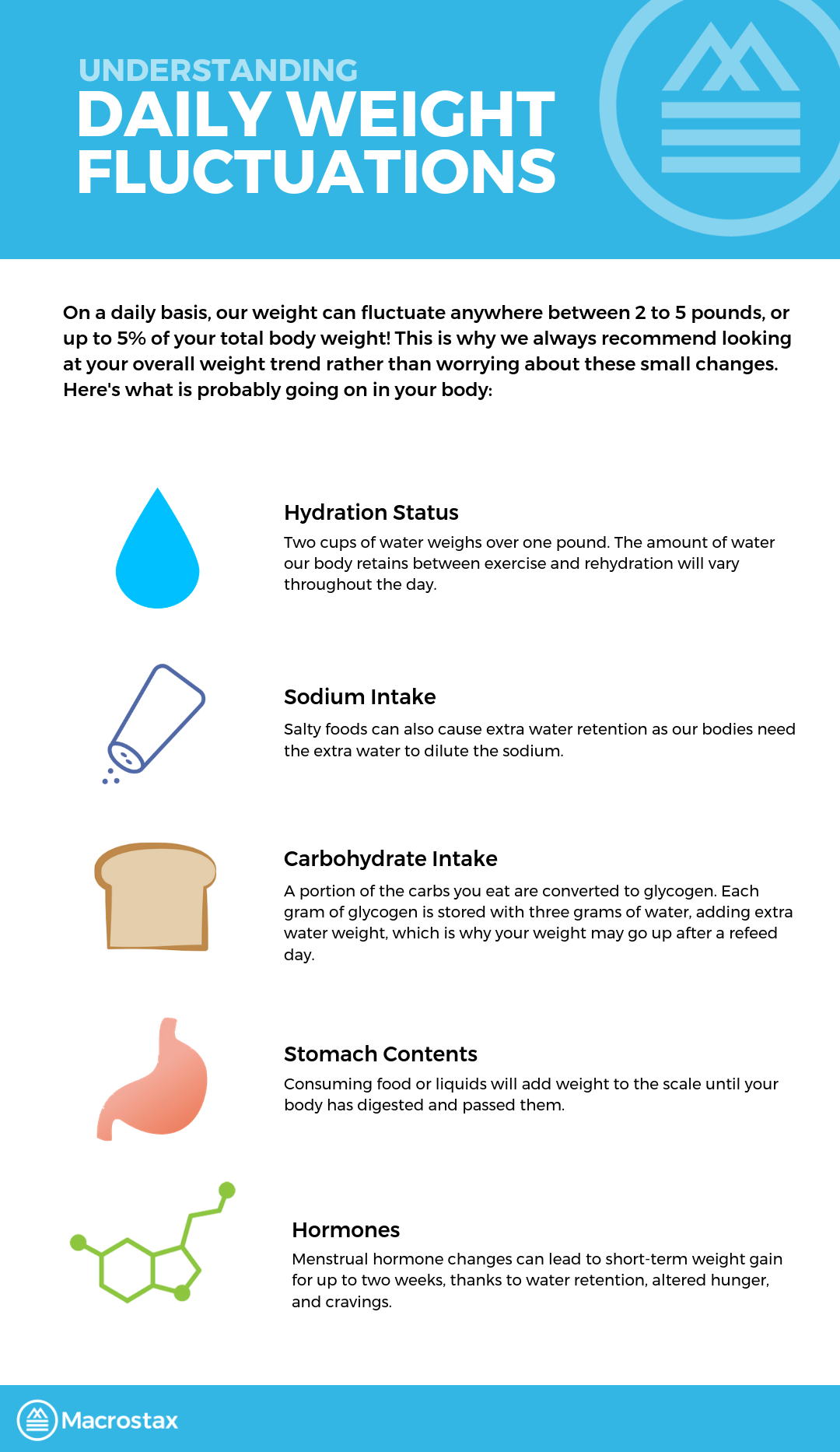

It is estimated that for individuals with a normal BMI, 60% of their body weight is composed of water. And it’s totally normal to experience water weight fluctuations of up to 5% daily! This is why your daily weight could vary between two and five pounds per day on average, although this number may be higher or lower depending on your weight.

There are five factors that usually contribute to body water (and therefore weight) fluctuations:

Hydration Status

Hydration status is a big contributing factor to weight fluctuations. Dehydration can lead to short-term weight loss (due to a deficit in water), whereas rehydration can lead to short-term weight gain. You’ve probably noticed that you might be several pounds lighter after a sweaty hot yoga session!

Each milliliter (mL) of water weighs one gram and two cups of water weighs roughly one pound. This is why a sweaty workout could easily cause a temporary weight dip, whereas chugging 20 ounces of water would have the opposite effect. The key here is to remember that these are temporary weight shifts!

Fun fact: experts say that even a three percent weight loss from fluid loss can lead to dehydration.

Carbohydrate Intake

You may have noticed that after high carb refeed days you “gain” a few pounds seemingly overnight. The good news is that this is most likely temporary, and due to the way that our body metabolizes carbohydrates (rather than true weight gain.)

One way the body stores extra carbohydrates is in the form of glycogen, which is mostly stored in the liver and muscles. Each gram of stored glycogen is stored along with three grams of water.

If you eat a high carb meal, your body likely uses some of those carbs to replenish your glycogen stores. And since your body stores water along with glycogen, your weight may increase. On the other hand, after an intense workout that depleted a lot of glycogen, your weight probably dipped thanks to lost glycogen and water.

This is partly why low carbohydrate diets or severely calorie-restricted diets can lead to initial rapid weight loss. That weight “loss” is partially due to glycogen and water losses, certainly not the healthiest method for long-term results or performance!

Sodium Intake

It’s well-known that high sodium (salt) intake can lead to water retention and an increase in blood pressure. When we eat salty foods like chips or takeout, our bodies respond by “holding on” to extra water to help dilute the sodium levels in our blood.

This increase in body fluid levels can cause symptoms such as puffy hands or feet, or a bloated feeling. Or, you may not notice any symptoms at all! Except for that number on the scale. A short-term weight gain after a higher salt meal (or a higher salt vacation) is expected, and should normalize as your eating pattern returns to baseline.

Hormones

Normal female hormone fluctuations throughout the month can lead to a pattern of fluid retention, or bloating, that also contributes to short-term weight shifts.

While the amount of water retention varies for each woman, one study found that women most often reported an increase in puffiness and bloating between ovulation and the first few days of menstruation. This is most likely due to variation in estrogen and progesterone levels throughout the month.

Researchers don’t yet know the exact mechanism that leads to fluid retention, and there’s no one “normal” monthly weight gain. But don’t be alarmed if you notice a pattern of weight gain in the second half of your cycle, it’s likely due to hormones!

Stomach Contents

Food weighs the same whether it’s on your plate or already in your stomach. A stomach full of food always weighs more than an emptier stomach, and the scale will reflect that! A recent meal can lead to an artificially high number on the scale.

Not to mention, after you eat a large meal your body is hard at work digesting, absorbing, and storing all the nutrients in your food. One study estimated that your body needs 100 ml (just under ½ cup) of water to metabolize 100 calories. So, the more you eat, the more water your body uses.

3 Tips for Tracking True Weight Trends

Now that we know how tricky body weight fluctuations can be, what is the best way to see past all the conflicting factors?

1.Weigh yourself at the same time of day. This will help reduce some variation due to stomach contents, exercise, and hydration.

2. Track your progress using the “Weigh-In” feature in the “Inputs” section of the Macrostax app. The graph will help you see longer-term (weekly or monthly) trends rather than focusing on day-to-day fluctuations.

3. Don’t forget about your weekly measurements or photos. These can be even more helpful tools than weight. Remember, it’s just a number! How you look, feel, and perform are usually more important indicators of how your nutrition is impacting your body composition.

References

- Bhutani et al. Composition of two-week change in body weight under unrestricted free-living conditions. Physiol Rep. 2017; 5(13): e13336.

- Shaheen et al. Public knowledge of dehydration and fluid intake practices: variation by participants’ characteristics. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 1346.

- Murray et al. Fundamentals of glycogen metabolism for coaches and athletes. Nutr Rev. 2018; 76(4): 243-259.

- Aburto et al. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013; 346: f1326.

- White et al. Fluid retention over the menstrual cycle: 1-year data from the prospective ovulation cohort. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011; 2011: 138451.